Madagascar: The Island That Drifted Away

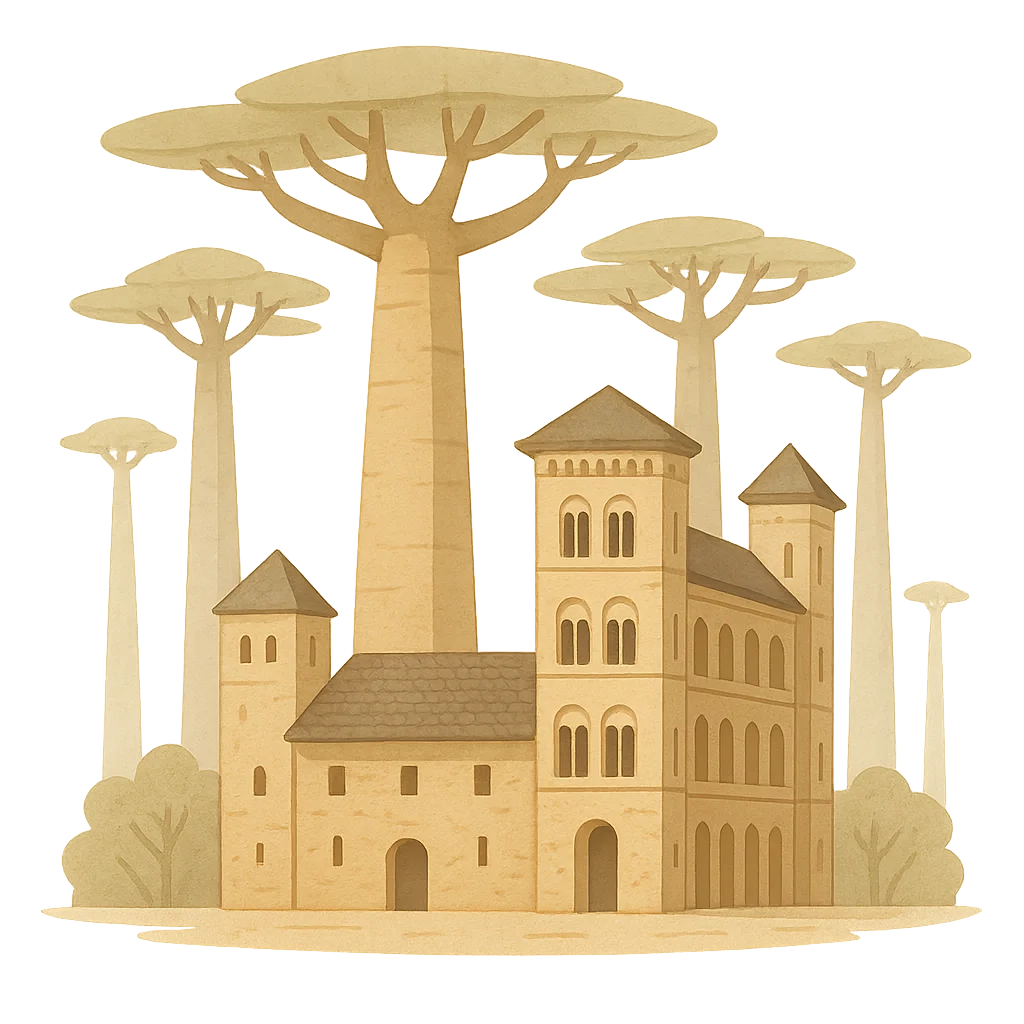

The warm waters of the Indian Ocean gently lap at my shores, a rhythm I have known for millions of years. Deep within my heart, in the dense green canopies of my rainforests, the calls of lemurs echo—a sound you can hear nowhere else on Earth. At dusk, the sky burns with orange and purple, and the silhouettes of my strange, wonderful baobab trees, which look as if they were planted upside down, stand against the fading light. The air itself carries my story, scented with the sweet spice of vanilla and the warm fragrance of cloves that grow in my rich, red soil. I am a world of vibrant chameleons that paint themselves with the colors of their surroundings and of fossa that prowl silently through the undergrowth. I am a land of contrasts, from jagged limestone pinnacles to serene coastlines. For ages, I existed as a secret, a jewel hidden in plain sight. I am a treasure chest of life, a world that drifted away and created its own story. I am Madagascar.

My story begins not with a single event, but with the slow, powerful dance of continents. Long, long ago, all the land on Earth was connected in a giant supercontinent called Gondwana. I was nestled right in the middle, tucked between Africa and India. But the world is always changing. About 165 million years ago, powerful forces deep within the Earth began to pull Gondwana apart. I felt the great rift as I broke away from the coast of Africa, a slow and monumental separation. For millions of years, I was still connected to what would become the Indian subcontinent, but then, around 88 million years ago, that final tether broke. I was set adrift, a massive island alone in the vast Indian Ocean. This long, lonely journey is the secret to my magic. Because I was so isolated, the plants and animals that found their way to my shores—perhaps on natural rafts of floating vegetation or carried by powerful winds—had me all to themselves. Without competition from creatures on the mainland, they evolved over millions of years into the fantastic and unique species you see today. My lemurs, with their dozens of different forms, my chameleons, with their incredible diversity, and the mysterious fossa all owe their existence to my solitary voyage through time.

For millions of years after I settled into my spot in the ocean, my only inhabitants were these incredible plants and animals. My forests grew thick and my rivers ran clear, untouched by human hands. The first human footprints on my shores did not appear until relatively recently in my long history. Sometime between 350 BCE and 550 CE, courageous seafarers from distant islands in Southeast Asia, known as Austronesians, navigated the vast and unpredictable Indian Ocean. They arrived in remarkable outrigger canoes, their sails catching the monsoon winds. These pioneers brought with them not just their families, but their culture, their language, and their knowledge of cultivating crops like rice, which would become a staple of Malagasy life. Centuries later, around the year 1000 CE, another wave of people arrived, this time from mainland Africa. Bantu-speaking groups crossed the Mozambique Channel, bringing their own traditions, music, and skills. On my soil, these two distinct groups of people met. They traded, they shared stories, and over time, they mingled and merged, creating the unique and vibrant Malagasy culture and a language that weaves together threads from both Asia and Africa. This fusion is the soul of my people.

As my human population grew, so did their societies. Small villages became larger communities, and eventually, kingdoms rose across my diverse landscapes. In my central highlands, a powerful kingdom began to take shape: the Kingdom of Imerina. In the late 1700s, a visionary king named Andrianampoinimerina began the ambitious work of uniting the island's many warring peoples under one rule, famously saying that the sea would be the boundary of his rice paddy. His son, King Radama I, continued this quest in the early 1800s, fostering relationships with European nations and modernizing his army and government. But contact with Europe, which had begun with the first Portuguese ships in the 1500s, brought new challenges. The desire for power and resources led France to invade, and on August 6th, 1896, I was formally declared a French colony. This was a difficult time for my people, a period of struggle where they fought to hold onto their identity. But their spirit of resilience never faded. After decades of perseverance, their dream of freedom was finally realized. On June 26th, 1960, a new flag was raised, and the joyous sounds of celebration echoed across the island as my people reclaimed their independence.

Today, I am more than just an island on a map. I am a living library of evolution, holding stories in my soil and my trees that go back millions of years. I am the cherished home of the Malagasy people, whose culture is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of Asia and Africa. My story is one of incredible resilience, both of nature and of humanity. But my future is not guaranteed. The very things that make me unique—my incredible forests and the rare creatures that live within them—are fragile. The modern world brings challenges, and my people are working hard to find a balance between their needs and the crucial work of conservation. Protecting my ecosystems is not just about saving lemurs and baobabs; it is about preserving a unique chapter in the story of life on Earth. My story is still being written every day, in every new leaf that unfurls and every child's laughter that rings through a village. Come, listen, and be part of it.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.