The Planet's Slow Heartbeat

To you, the ground beneath your feet feels solid, a dependable stage for your life. You build your homes on it, run across its fields, and trust it to be still. But I know its secret. I am the quiet, immense power that pushes mountains a few millimeters higher each year, a growth so slow you could never notice. I am the force that nudges continents apart, widening the great oceans inch by inch over a lifetime. Sometimes, my energy builds and releases in a sudden, violent shudder that you call an earthquake, a frightening reminder that the planet’s surface is not one solid piece. Think of the world map as a photograph of a giant jigsaw puzzle, its pieces scattered and separated by water. If you look closely, you might notice how the curve of one continent seems to echo the coastline of another, thousands of miles away. They are clues to a time when the puzzle was whole, a memory I have held for hundreds of millions of years. I am the planet’s slow, powerful heartbeat. I am Plate Tectonics.

For centuries, humans looked at their maps and felt a flicker of recognition. As early as the 1500s, a cartographer named Abraham Ortelius noted how the coasts of the Americas seemed to fit perfectly against the coasts of Europe and Africa, like torn pieces of paper. But it was just a curious observation, a geographical coincidence. It took a truly imaginative and persistent mind to see the grander picture. That mind belonged to a German meteorologist and explorer named Alfred Wegener. On January 6th, 1912, he stood before a group of skeptical scientists and proposed a radical idea he called 'Continental Drift.' He argued that all the continents had once been joined together in a single supercontinent he named Pangaea, and had since drifted apart. His evidence was compelling. He pointed to fossils of the same tropical plants found in both the icy Arctic and balmy Africa. He showed how ancient reptile fossils, from creatures that could never have swum an ocean, were found on the separate shores of South America and Africa. He even traced ancient mountain ranges that appeared to have been sliced in two, with one half in North America and the other in northern Europe. The evidence was all there, but the world’s leading scientists dismissed him. They all asked the same question: What force could possibly be strong enough to move an entire continent? It was a question Alfred couldn’t answer. His brilliant idea had no motor, no engine to explain the movement. He spent the rest of his life defending his theory, but he died on an expedition in Greenland in 1930, his revolutionary idea still considered fringe science.

For decades, Alfred Wegener’s theory lay dormant, a fascinating but unproven hypothesis. The key to unlocking my secret wasn’t on the land he had studied so carefully, but hidden deep beneath the waves, in a world of crushing pressure and eternal darkness. In the 1950s, after World War II, scientists began mapping the ocean floor in detail for the first time. A team at Columbia University, led by Bruce Heezen, sent ships out to collect depth soundings from the Atlantic. Back in the lab, a brilliant geologist named Marie Tharp was tasked with the painstaking work of turning those raw numbers into maps. As she plotted the data point by point, an incredible picture emerged from the chaos. She discovered a colossal underwater mountain range running down the center of the Atlantic Ocean, which she called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Even more astonishing, she found a deep rift valley, a massive trench, running along the very crest of the ridge. She theorized that this was a place where the seafloor was splitting apart and new crust was being formed from magma bubbling up from below. This was it. This was the engine. The seafloor was spreading, acting like a giant conveyor belt that carried the continents along with it. At first, her colleague Bruce Heezen dismissed her idea as 'girl talk,' but when they compared her map to earthquake data, they found that earthquakes lined up perfectly with the rift valley. It was undeniable proof. Marie Tharp's meticulous work provided the mechanism for Continental Drift, finally vindicating Alfred Wegener nearly thirty years after his death.

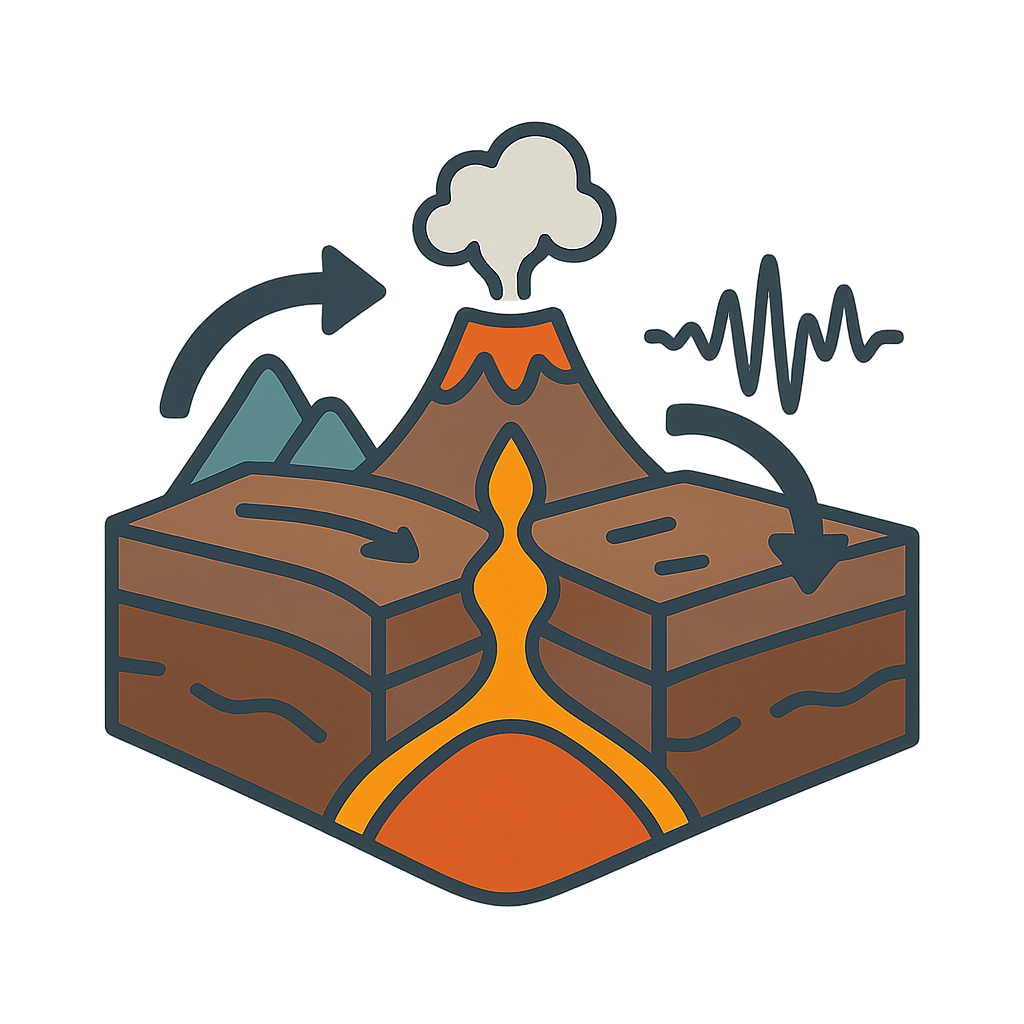

Now you understand how I work. The Earth's crust isn't one solid shell; it is broken into massive plates that float and glide upon the hotter, softer mantle beneath. My movements are varied and shape everything you see. Where my plates collide with unstoppable force, the crust buckles and folds, thrusting rock skyward to create magnificent mountain ranges like the Himalayas. Where they grind and slide past one another, tension builds along massive cracks called faults, like the San Andreas Fault in California. When that tension snaps, the ground shakes violently. And deep in the oceans, at ridges like the one Marie Tharp discovered, my plates pull apart, allowing new crust to be born, continuously renewing the planet's skin. This process isn't meant to be frightening; it is a vital sign of a healthy, dynamic planet. Understanding me allows scientists to better predict where earthquakes and volcanoes might occur, helping to save lives. It helps geologists locate valuable resources deep within the Earth. I am the constant, slow dance that shapes your world, a powerful reminder that nothing is truly permanent. I am always at work, creating new lands, new mountains, and new oceans, ensuring that the story of our planet is one of endless, beautiful change.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer