Orville Wright and the First Flight

My name is Orville Wright, and alongside my older brother Wilbur, I had a dream that many people thought was impossible. We wanted to fly. It all started when we were just boys back in Dayton, Ohio. Our father, a traveling bishop, once brought us home a toy helicopter. It was a simple thing, made of paper, bamboo, and cork, powered by a twisted rubber band. When he tossed it into the air, it fluttered up to the ceiling. Wilbur and I were mesmerized. We built copies of it, each one bigger than the last, and from that moment on, the idea of soaring through the sky like a bird captured our imaginations. As we grew up, we opened our own business, the Wright Cycle Company. You might wonder what bicycles have to do with airplanes, but they taught us everything. We learned how to balance a moving object, how to build structures that were both lightweight and incredibly strong, and how to solve mechanical problems with our own hands. Every bicycle we built and repaired was a lesson in engineering that we would later apply to the great puzzle of flight. Our partnership was the heart of it all. Wilbur was thoughtful and visionary, while I was often the more optimistic and hands-on mechanic. Together, we believed we could solve a problem that had stumped brilliant minds for centuries.

Our bicycle shop was our workshop, but the sky was our laboratory. We began by reading every book and paper we could find about aeronautics. We studied the work of pioneers like Otto Lilienthal, a German glider pilot. But we soon discovered that much of the published data was unreliable. If we wanted to succeed, we had to figure things out for ourselves. So, in our shop, we built a wind tunnel—a six-foot-long wooden box with a fan at one end. Inside, we tested over two hundred different miniature wing designs, carefully measuring how they reacted to the flow of air. This research was critical, as it allowed us to design a wing that would actually provide enough lift. Our most important invention, however, was a system for control. We spent hours watching birds, noticing how they twisted the tips of their wings to turn and maintain balance. This observation led us to an idea we called 'wing-warping.' By twisting or 'warping' the wings of our glider using a set of cables connected to a hip cradle the pilot lay in, we could control the machine's roll and steer it through the air. To test our ideas, we needed a place with strong, steady winds and soft ground for our inevitable crashes. We found the perfect spot in a remote, windswept village on the coast of North Carolina: Kitty Hawk. For several years, from 1900 to 1902, we hauled our gliders to the giant sand dunes there. We faced countless setbacks—broken spars, torn fabric, and frustrating flights that barely left the ground. Each failure was a lesson, pushing us to refine our designs and never give up.

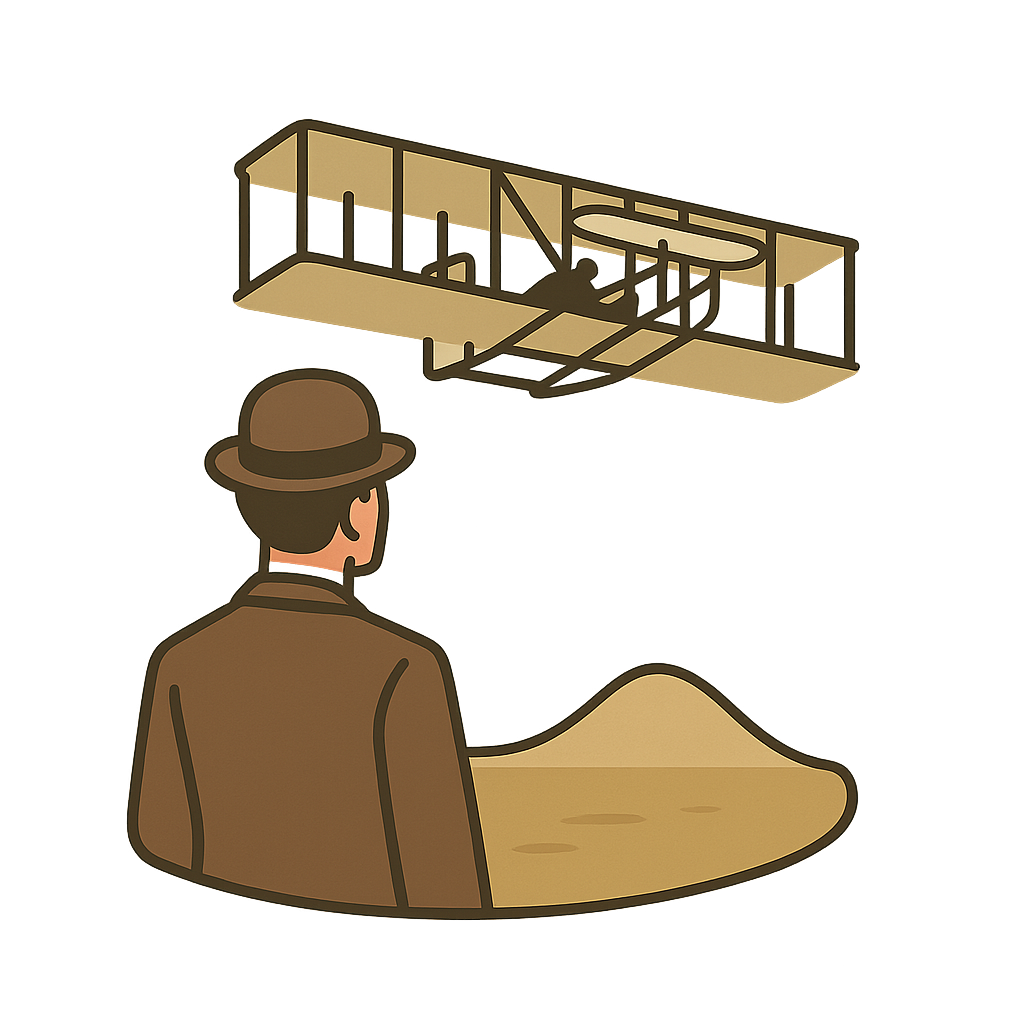

Finally, after years of tireless work, the day arrived. It was December 17, 1903. The morning air at Kitty Hawk was bitterly cold, and a fierce wind gusted across the flat sands. We knew the strong headwind would help lift our machine, which we called the Wright Flyer, but it also made the attempt more dangerous. A small group of men from the local lifesaving station were our only witnesses. Since we both had worked equally on the Flyer, Wilbur and I tossed a coin to see who would make the first attempt. I won. I climbed aboard, settling myself flat on my stomach on the lower wing, my hands gripping the controls. My heart pounded with a mix of excitement and anxiety. Wilbur started our small, four-cylinder engine, which we had designed and built ourselves. It sputtered to life with a deafening roar, and the two propellers behind me began to spin. With a final check, I signaled I was ready. The machine began to move down the 60-foot wooden launch rail we had laid on the sand. It rattled and shook, picking up speed. Then, it happened. I felt a change, a lightness, as the wheels lifted from the rail. The ground fell away beneath me. I was flying. For a breathtaking, heart-stopping moment, I was no longer bound to the earth. The machine dipped and swayed in the wind, and I had to work the controls constantly to keep it level. I flew for just 12 seconds, covering a distance of 120 feet—shorter than the wingspan of a modern jumbo jet—but in that moment, everything changed. We had done it. We had achieved powered, controlled flight.

When the Flyer skidded to a stop on the sand, the flight was over, but a new age had just begun. Wilbur ran to my side, and though we didn't shout or celebrate wildly, we both shared a look of profound accomplishment. We knew the world would never be the same. That first flight was short, but it was just the start. We weren't finished for the day. We took turns, making three more flights. Each one was a little longer, a little better. On the fourth and final flight of the morning, Wilbur was at the controls. He managed to stay in the air for an incredible 59 seconds and flew 852 feet, proving that our success wasn't a fluke. We had truly unlocked the secret of flight. All those years of studying, building, and failing, all the moments of doubt and frustration, had led to this triumph. We had shown that with curiosity, a willingness to challenge old ideas, and the perseverance to keep trying no matter how many times you fail, even the wildest dreams can take flight. Our journey began with a simple toy, but by working together, my brother and I were able to give humanity the gift of wings. And it all started with those twelve seconds in the cold December wind.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer