I Am the Barometer, a Measurer of the Unseen

Before I existed, the world was wrapped in a great mystery. People felt the wind on their faces, watched clouds drift across the sky, and felt the chill of a coming storm, but they didn't truly understand the air around them. They lived at the bottom of a vast, invisible ocean, an ocean made not of water, but of air that stretched miles and miles above their heads. They didn't know that this air had weight, that it was constantly pressing down on the land, the sea, and on their very own shoulders. This constant, gentle push is called atmospheric pressure. It was a force that was felt but never seen, a power that influenced their lives but remained unexplained. I am the Barometer, and I was born from a deep curiosity to see the unseen and to measure this invisible ocean. My story begins in a time of great thinkers and bold questions, when a few brilliant minds dared to believe that even the air itself held secrets that could be unlocked. I was the key they forged, a simple instrument designed to give a voice to the silent pressure of the sky.

My creation took place in Italy, in the year 1643. My maker was a clever and thoughtful scientist named Evangelista Torricelli. He had been a student of the great Galileo Galilei, who had taught him to question everything and to seek answers through experiments. Torricelli was fascinated by a practical problem that had stumped the cleverest engineers of his day: why couldn't water pumps lift water any higher than about 34 feet. The old answer was that “nature abhors a vacuum,” meaning nature would always rush to fill an empty space. But if that were true, why did it stop working at 34 feet. Torricelli suspected something else was at play. He theorized that the weight of the ocean of air was pushing down on the water in the well, and that this pressure was what forced the water up the pipe. The pump was just creating a space for the air to push the water into. He reasoned that if he used a liquid much heavier than water, the column of air pressure could not hold it up as high. He chose mercury, a shimmering silver liquid almost fourteen times denser than water. On a day that would change science forever, he took a glass tube about a meter long, sealed at one end, and filled it to the brim with the heavy mercury. With his finger over the open end, he carefully turned it upside down and submerged it in a dish also filled with mercury. When he removed his finger, the moment of truth arrived. The column of mercury inside the tube fell, but only a little. It stopped at a height of about 76 centimeters, leaving an empty space at the top. I was born in that moment. That empty space was the first sustained human-made vacuum, and the height of the mercury was a perfect measurement of the atmosphere’s pressure. The weight of the air pressing on the mercury in the dish was holding up the entire column of silver liquid inside me. I had made the invisible visible.

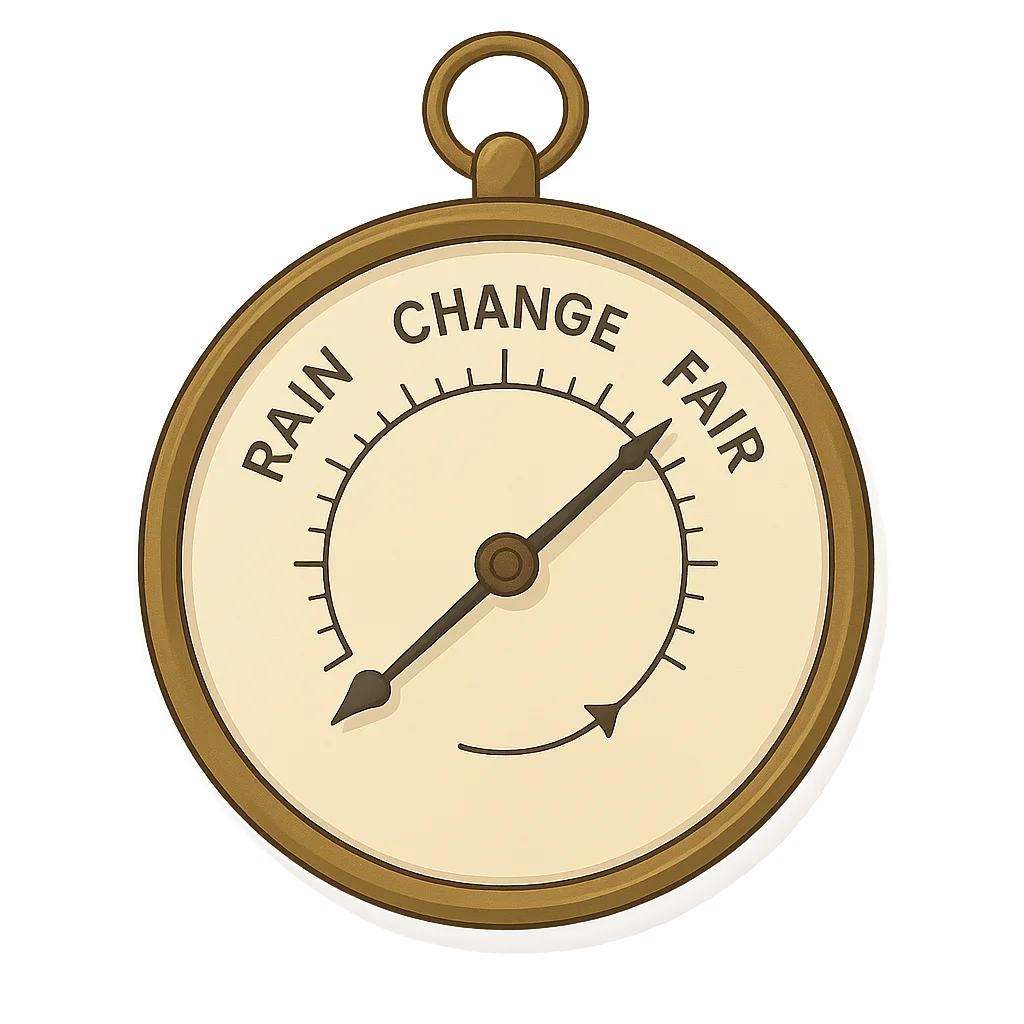

My purpose became clear almost immediately. I was not just a curiosity for a laboratory; I was a tool for exploring the world. In 1648, a French scientist and philosopher named Blaise Pascal heard of my existence and had a brilliant idea. He believed that if the air was an ocean, then its pressure must be lower at the top than at the bottom. To prove it, he arranged for his brother-in-law to carry one of my siblings up a tall mountain in France, the Puy de Dôme, which stood nearly 1,500 meters high. As I was carried up the winding path, I felt the weight of the air above me lessen. Inside my glass tube, the column of mercury slowly sank lower and lower. At the summit, my reading was significantly lower than the identical barometer left at the mountain's base. The experiment was a resounding success. It proved that the atmosphere gets thinner the higher you go. Soon after, people began to notice another of my talents. My mercury level didn't just change with altitude; it changed with the weather. Before a storm rolled in, the air pressure would drop, and my mercury would fall. On clear, calm days, the pressure was high, and my mercury would rise. I had become the world's first reliable weather forecaster, a vital guide for sailors preparing for a voyage and farmers tending their crops.

Centuries have passed since my birth as a simple glass tube of mercury. Today, you will not find me in that form very often. I have evolved. I now live as a tiny, precise digital sensor inside your smartphone, helping it know its altitude. I am an essential part of every airplane's instrument panel, telling pilots how high they are flying. I exist in sophisticated weather stations all over the globe, constantly monitoring the atmosphere to predict hurricanes and keep people safe. Though my form has changed, my soul and my purpose remain the same. I still measure the pressure of the invisible ocean of air around us. My story is a reminder that the greatest discoveries often begin with a simple question about the world around us. By daring to measure what seems immeasurable, we gain the power to understand, to explore, and to protect our world and each other. Never stop being curious about the unseen forces that shape your life.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer