The Weight of the Sky

Hello, my name is Barometer. Before I came along, the world was full of invisible mysteries. One of the biggest puzzles was in a beautiful city called Florence, in Italy. The well-diggers and miners there were very clever, and they had built amazing pumps to pull water up from deep in the ground. But they hit a strange wall. No matter how powerful their pumps were, they could never lift the water higher than about thirty-four feet. It was as if an invisible ceiling was pushing the water down. They scratched their heads and argued, but no one could figure it out. Then, a brilliant scientist named Evangelista Torricelli had a wild idea. He thought the answer was not in the ground or in the pumps, but all around them. He imagined that the air, which feels like nothing at all, actually had weight. He believed it was constantly pushing down on everything, like a great, invisible blanket. This push, he thought, was what was stopping the water from rising any higher.

It was in the year 1643 that Torricelli finally brought me to life to prove his idea. He described our world as being at the bottom of a giant 'sea of air.' He knew that testing his idea with water would require a ridiculously tall glass tube, so he chose something much heavier: a fascinating, silvery liquid called mercury. It was so dense that he believed the sea of air would not be able to hold up a very tall column of it. I remember it so clearly. He took a long glass tube, sealed at one end, and carefully filled it to the very brim with shimmering mercury. Then, his heart likely pounding with excitement, he placed his finger over the open end and turned me upside down, plunging the open end into a dish that also held mercury. What happened next was magic. The mercury in the tube slid down a little, but it did not all run out. A column of silver, about thirty inches tall, stood suspended inside the glass, held up by nothing but the invisible push of the air on the mercury in the dish below. A small, empty space was left at the very top of my tube. That was the moment I was born. I was the very first barometer, and I was showing the world the true weight of the sky.

My existence was exciting, but it was another scientist who made me famous all over Europe. A man named Blaise Pascal heard about me and was fascinated. He wanted to test Torricelli's 'sea of air' theory even further. So, on September 19th, 1648, he arranged for an incredible experiment. He asked his brother-in-law to take one of my cousins, a barometer just like me, and carry it up a very tall mountain in France. As they climbed higher and higher, something amazing happened. The column of mercury inside my cousin began to drop. At the very top of the mountain, the mercury was several inches lower than it had been at the bottom. This was the proof everyone needed. The sea of air was deeper and heavier at the bottom of the mountain and thinner and lighter at the top. Soon, people noticed something else. Before a big storm rolled in, the air would become lighter, and the mercury in my tube would fall. When the weather was clear and sunny, the air pressed down harder, and the mercury would rise. I had become a weather forecaster. For sailors on the vast ocean and farmers tending their fields, this was a miracle. I could warn them of coming storms, giving them time to prepare and stay safe.

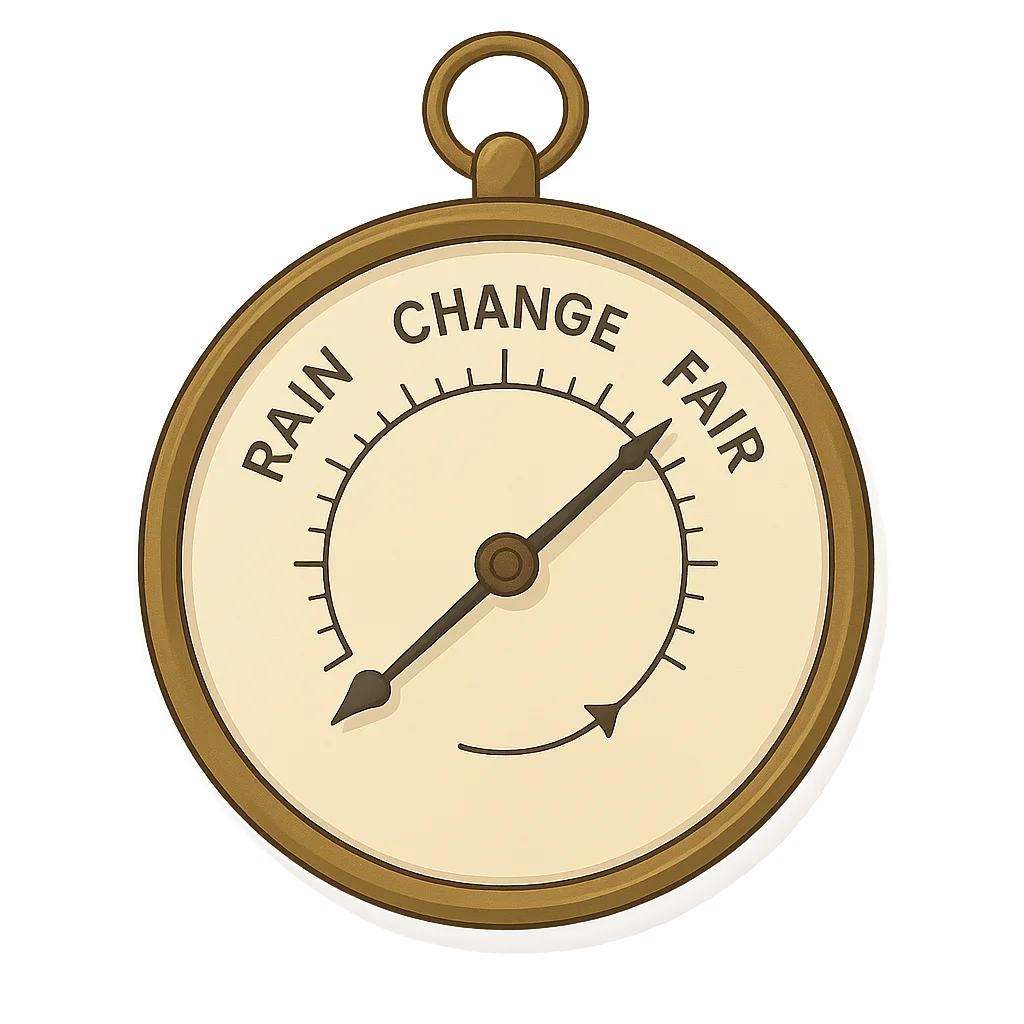

I do not always look like a glass tube full of silvery liquid anymore. Over hundreds of years, I have evolved. Today, you might see me as a handsome brass dial hanging on a wall, with a needle that points to 'Stormy' or 'Fair.' I can be a set of numbers on a digital weather station in your home. I have even become so small that I can live inside your smartphone or your watch, constantly measuring the air's pressure to help with your weather app or track your altitude when you are hiking. Though I have changed my appearance, my job is exactly the same as it was on that exciting day in 1643. I still measure the invisible push of the air around us. I help airplane pilots fly safely through the skies and meteorologists predict the weather for everyone. I am a reminder that sometimes, the most powerful forces are the ones you cannot see, and it all started with a curious idea about living at the bottom of a sea of air.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer