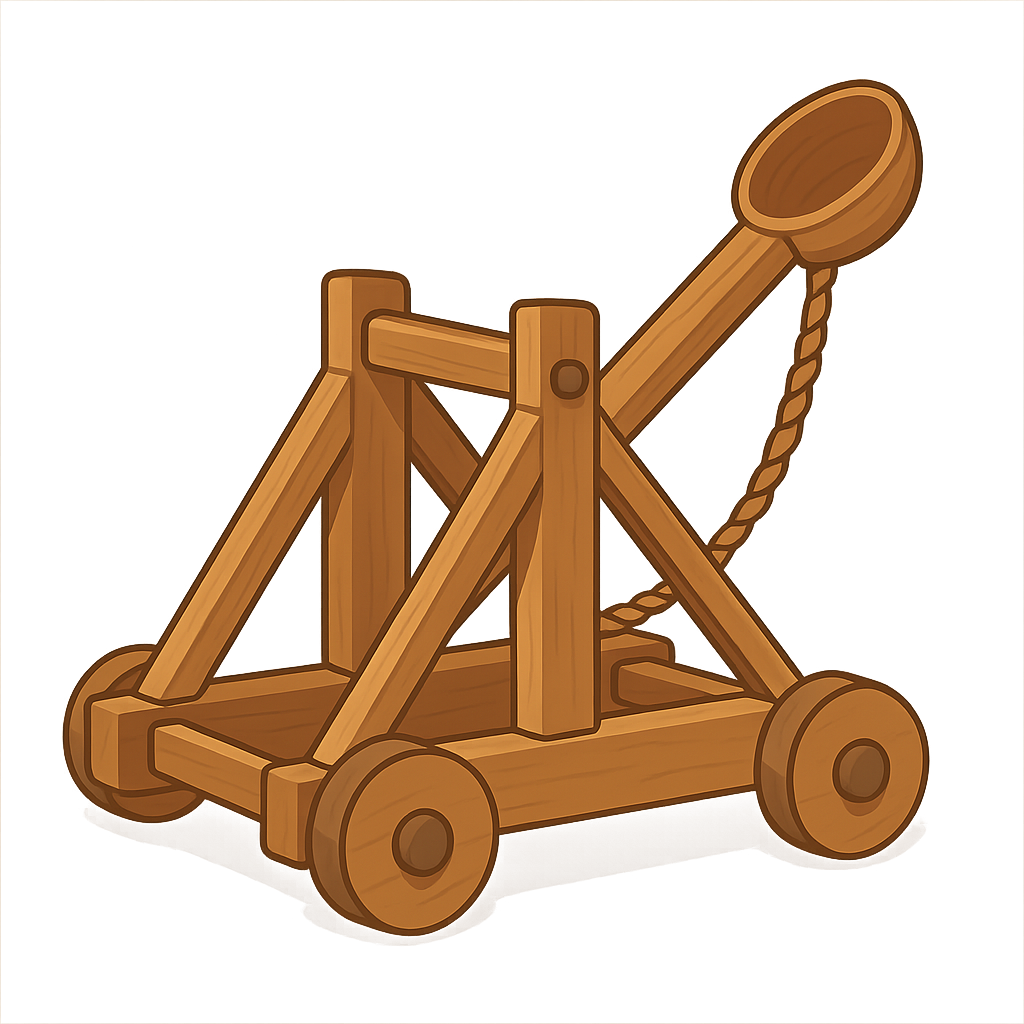

I Am the Catapult: A Story of Stone and Timber

Before I existed, the world was a very stubborn place, full of stone walls that refused to budge. Imagine being a soldier, staring up at the towering defenses of an enemy city. You could wait for months, hoping the people inside would run out of food. You could try to climb the walls on flimsy ladders or push a heavy battering ram against a gate, all while arrows and rocks rained down on you. It was slow, dangerous, and terribly frustrating. I was born from that frustration. My story begins in a sun-baked city of ancient Greece called Syracuse, around the year 399 BCE. A clever and ambitious ruler named Dionysius I was tired of these endless sieges. He gathered the brightest engineers, thinkers, and craftspeople of his time and gave them a challenge: “I need a weapon,” he declared, “that can throw a stone farther and harder than any man. I need something that can shatter walls from a distance.” They were tasked with inventing a solution to an age-old problem, and that solution was me. I am the Catapult, and I was created to change the very nature of warfare.

My first form was humble, more like a monstrous crossbow than the mighty siege engine I would become. The engineers called it a gastraphetes, or “belly-bow,” because a soldier had to brace it against his stomach to draw back the powerful bowstring. It was a good start, but it wasn't enough to crumble a fortress. The real breakthrough, the spark of genius that gave me my true power, was the discovery of torsion. Instead of a flexible bow, my creators built a rigid wooden frame. Through this frame, they threaded massive bundles of rope made from twisted animal sinew and horsehair. They twisted these ropes tighter and tighter, like winding up a giant rubber band, until they hummed with an almost terrifying amount of stored energy. This was my heart, my muscle. I can still remember the day they first tested me. My timbers creaked and groaned under the immense strain as they winched my long throwing arm back. A heavy stone was placed in my sling. A craftsman shouted, “Release!” and with a deafening crack, the tension was unleashed. My arm whipped forward with a force that shook the ground, and the stone became a blur. It soared through the air in a perfect arc, silent for a moment before it smashed into a practice wall, reducing it to a cloud of dust and splinters. It was a beautiful, terrible sight. Soon, great leaders recognized my potential. Philip II of Macedon, a tactical genius, used me not just to break cities but to control battlefields. His son, Alexander the Great, took me with him on his legendary conquests, and I became his unstoppable fist, knocking down the gates of empires from Greece to India.

I am not one single machine; I am an idea that grew and changed with the people who used me. After my time with the Greeks, I was adopted by the master builders of the ancient world: the Romans. They loved my efficiency and power. Roman engineers perfected my design, making me more accurate, more durable, and sometimes even mobile on wheels. They gave me fearsome names, like the Onager, which means “wild donkey,” because my whole frame would kick violently backward when I fired. Every Roman legion had a battery of catapults, and I helped them conquer and control their vast empire for centuries. But my evolution didn't stop there. As the Roman Empire fell and the Middle Ages began, castles became bigger and stronger than ever before. To defeat them, I had to become bigger and stronger, too. That is when my mighty cousin was born: the Trebuchet. While I relied on the stored energy of twisted ropes, the trebuchet was a master of gravity and leverage. It was a colossal see-saw. On one end of its long arm was a sling for a projectile, and on the other, a massive box filled with tons of rock and lead. When the counterweight was dropped, the arm would swing upward with incredible force, launching boulders the size of cows. It was a magnificent, awe-inspiring machine, and I was proud to call it family. For over a thousand years, from the shores of Syracuse to the castles of medieval Europe, my kind ruled the art of the siege.

My reign, however, could not last forever. A new sound eventually echoed across the battlefields of the world—the deafening boom of gunpowder. The cannon arrived, a weapon of fire and iron that could hurl metal balls with even greater force and accuracy than I ever could. My wooden frame and twisted ropes were no match for this new technology, and slowly, I was retired from active duty. But just because I no longer smash castle walls doesn't mean I am gone. My spirit, the scientific principles that gave me life, is all around you. Every time you see a lever pry something open, or watch a diver spring into the air from a diving board, you are seeing my ideas at work. I am the master of potential and kinetic energy—the storing of power and its explosive release. You can even see my direct descendant in one of the most powerful machines on Earth: the catapults on aircraft carriers that fling fighter jets from a standstill to flying speed in just two seconds. My time as a weapon of war may be over, but the clever idea that sparked my creation—the desire to throw something farther and faster—is a legacy that will never fade.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.