I Am a Thread of Light

A Messenger of Light

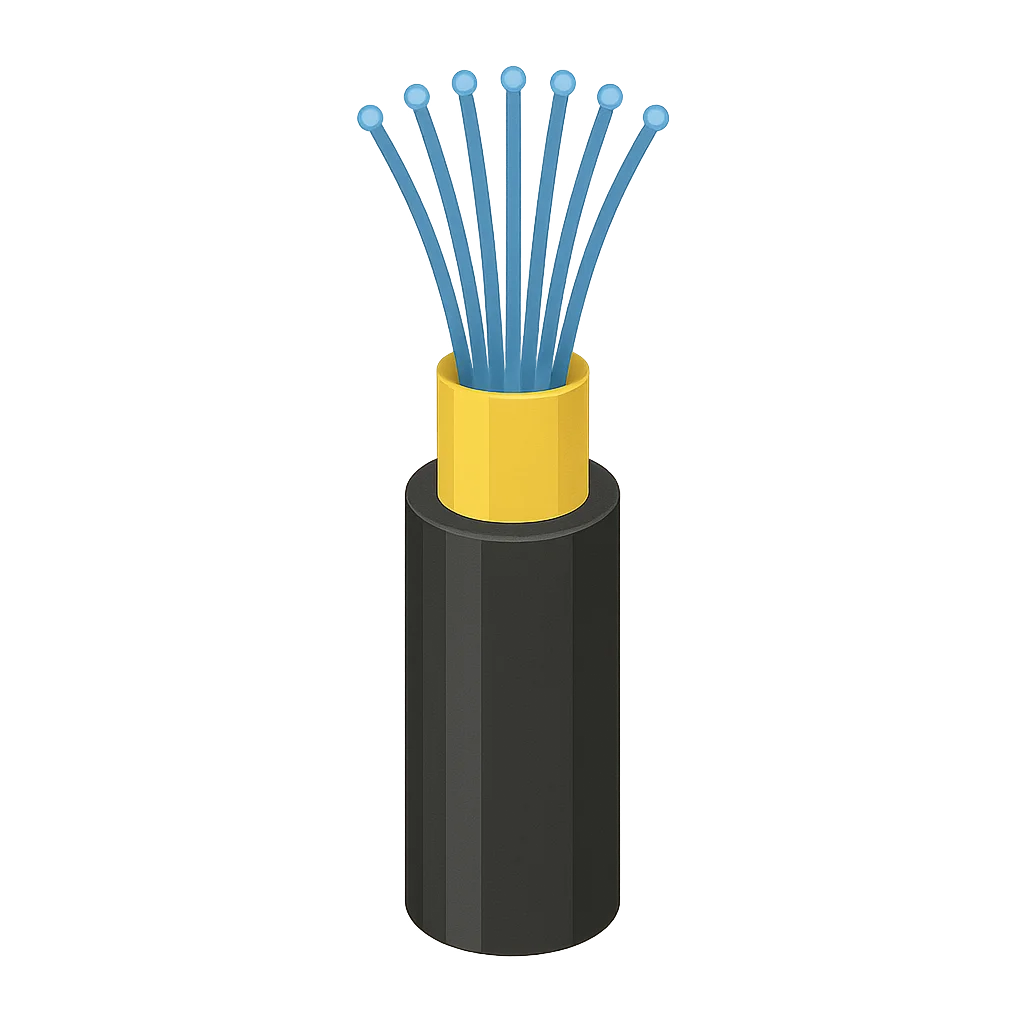

Before you know my name, you must understand what I am. I am a messenger, a carrier of stories, voices, and dreams. I am a single, impossibly thin strand of glass, purer than a mountain spring and more flexible than a willow branch. My official name is a Fiber Optic Cable, and my purpose is to carry information in its fastest, most brilliant form: light. Imagine a pulse of light, a tiny flicker containing a word, a picture, or a note of a song, and I am the path it travels. This light races through my core at nearly the speed of light itself, a silent, invisible river of data. But it wasn't always this way. For centuries, the world was a vast and disconnected place. Messages traveled at the speed of a horse, a ship, or later, a sluggish electrical current through thick, heavy copper wires buried underground or laid on the ocean floor. Sending a message across the sea could take days or weeks, and the signal would often weaken, becoming a faint whisper by the time it arrived. The world was growing, and its people yearned to connect faster and more clearly. They needed a new kind of messenger, one that was not bound by the weight of metal or the slowness of the old ways. They needed a messenger of light.

The Dream of a Glass Thread

My story began not in a laboratory, but as a flicker of an idea in the minds of curious scientists. Long before I was born, in the 1840s, a Swiss physicist named Daniel Colladon was playing with water and light. In a darkened room, he shone a lamp through a container of water, letting a stream pour from a hole in its side. He noticed something magical. The light did not travel in a straight line out of the stream. Instead, it bent and followed the curve of the water, trapped within the flowing jet. He had demonstrated a principle called total internal reflection, proving that light could be guided along a path. It was a beautiful curiosity, a parlour trick for a while, but the seed of my existence had been planted. For over a century, that seed lay dormant. Then, in the bustling, forward-thinking era of the 1960s, the world was ready for a great leap. An engineer and physicist named Charles K. Kao, working in England, looked at the world's communication networks and saw their limits. He knew copper wires could only do so much. He had a revolutionary vision. On a day in 1966, he and his colleague George Hockham published a paper that was, in essence, my blueprint. They proposed that if glass could be made almost perfectly pure, a fiber drawn from it could carry light signals over enormous distances with very little loss of strength. At the time, glass was simply not pure enough; light sent into a glass rod would fade to nothing in just a few feet. Many thought his idea was impossible, a fantasy. But Charles K. Kao was a visionary. He saw me not as I was, but as I could be. He imagined a future where these glass threads would encircle the globe, a web of light connecting all of humanity. He gave scientists a clear target, a challenge that sparked a technological race.

My Birth in a Furnace

To be born, I required a miracle of purity. The challenge Charles K. Kao had laid down was monumental. The glass needed for me had to be so transparent that you could see through a window of it that was miles thick. The ordinary glass of a window pane was, by comparison, as murky as a swamp. The task fell to a team of brilliant and determined scientists at a company in America called Corning Glass Works. Their names were Robert Maurer, Donald Keck, and Peter Schultz, and they became my creators. For years, they toiled in their laboratory, experimenting with different methods to create this impossibly pure glass. They worked with fused silica, a type of glass that had the potential for high purity, but it was difficult to work with. They tried again and again, facing countless failures. Their early attempts produced glass that was better, but still not good enough. The light signals still faded far too quickly. But they were relentless. They believed in the dream of a messenger of light. Then, one day in August of 1970, came the breakthrough. Donald Keck was analyzing their latest fiber attempt when he saw a result on his equipment so incredible he didn't believe it at first. The light signal was surviving, traveling through the fiber with astonishingly little loss. He famously wrote in his notebook, “Whoopee.” They had done it. They had created the first practical low-loss optical fiber. They had created me. From that moment, my physical creation began. I was born in the intense heat of a furnace, where a carefully crafted cylinder of that ultrapure glass was heated until it was molten. Then, I was pulled, stretched out into a continuous, perfect thread thinner than a single human hair but, ounce for ounce, stronger than steel. I was finally ready to begin my work.

Connecting the World at the Speed of Light

My first real job came in 1977. A length of me was laid beneath the bustling streets of Chicago to carry live telephone traffic. For the first time, people’s voices were being transmitted as pulses of light through my glass core, and the calls were clearer than ever before. This was just the beginning. Soon, I was stretching across continents and diving deep beneath the oceans, replacing the old, cumbersome copper cables. I became the backbone of a new global network, an invention you now know as the internet. Every time you watch a video, talk to a loved one on a video call, or explore a new world in an online game, my siblings and I are the ones making it possible. We carry the data from a server thousands of miles away to your screen in a fraction of a second. I also found work in other places. Doctors use bundles of my fibers in endoscopes to see inside the human body without surgery, guiding their hands with the light I provide. Engineers use me to monitor the structural health of bridges and buildings. My journey from a scientific curiosity to the nervous system of the modern world has been remarkable. I was born from a dream of connecting people, and today, that is what I do. I carry the world’s knowledge, its art, its commerce, and most importantly, its conversations. I am a simple thread of glass, but by carrying light, I help bring the world, and all of you, a little closer together.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.