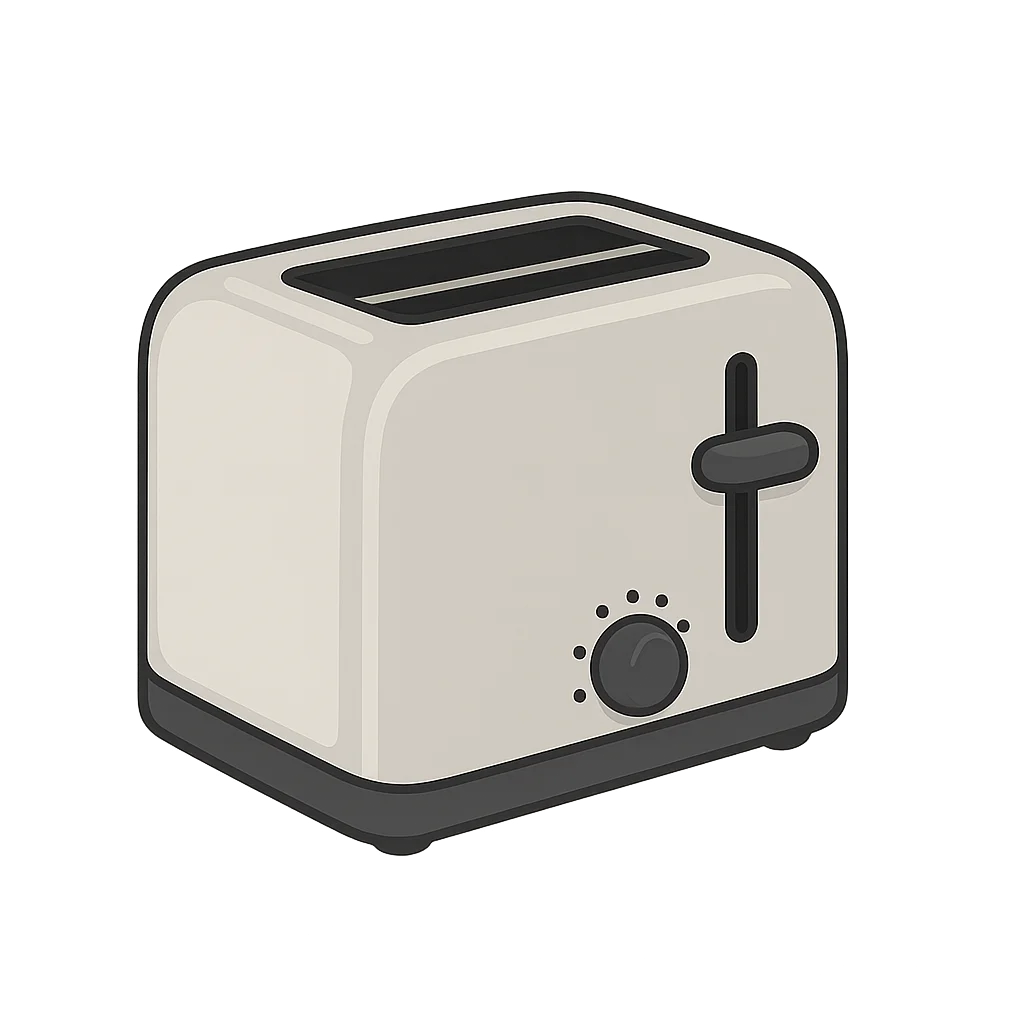

The Tale of a Toasty Morning

Before I could bring a golden-brown crispness to your morning routine, things were quite a bit messier. My name is the Toaster, and my story begins not with a pop, but with a flicker of fire and a lot of patience. Imagine a time before I existed, when the idea of perfect toast was a gamble. In kitchens lit by gas lamps or early, dim electric bulbs, people would try to toast bread by holding a slice on a long metal fork over an open flame. It was a delicate, and often dangerous, dance. A moment of distraction, and the bread would turn from warm to a blackened, smoky crisp. Fingers were frequently singed, and the toast, if you could call it that, was often unevenly cooked—charred on the edges and soft in the middle. Some tried placing racks directly on stovetops, but that was just as tricky. The world was filling with new electrical wonders, and kitchens were slowly transforming. People wanted convenience and reliability. They needed a safer, more predictable way to make their breakfast, and that growing need was the spark that would eventually give me life. The world was ready for an invention that could tame the heat and deliver a perfect slice of toast, every single time.

My true birth, however, couldn't happen with just electricity alone. I needed a very special heart, something that could glow with intense heat but not burn out or melt. For years, this was a puzzle that stumped inventors. Then, in 1905, a brilliant metallurgist named Albert L. Marsh cracked the code. He created an alloy of nickel and chromium and called it nichrome. This wasn't just any wire; it was the magic ingredient I had been waiting for. Nichrome wire could withstand incredible temperatures and glow a brilliant, fiery orange without failing. It was the key that unlocked my potential. A few years later, in 1909, a man named Frank Shailor, working for a company called General Electric, used this amazing wire to design the first commercially successful version of me. They called me the D-12. I wasn't very glamorous back then. I was essentially an open cage of metal with those amazing nichrome wires strung across the middle. A person would place a slice of bread into my side, and my wires would glow to life, toasting one side. It was a marvel, but it still required constant supervision. Once one side was brown, you had to manually flip the hot slice to toast the other. I was a step into the modern age, but I knew my journey was far from over. I felt proud, but I was still just a simple heater, waiting for my next great idea.

My moment of transformation, the leap that made me a true kitchen legend, came from a place of simple frustration. In a factory cafeteria in Stillwater, Minnesota, an inventor named Charles Strite was tired of eating burnt toast. Day after day, the kitchen staff would get distracted, and the toast from simple toasters like my D-12 model would end up charred. Strite knew there had to be a better way. He thought, what if a machine could handle the timing all by itself? This thought sparked an ingenious idea. Working in his spare time, he began tinkering. On May 29th, 1919, he filed a patent for his creation, which he perfected and released in 1921. He had designed a version of me with two incredible new features: a variable timer and a spring-loaded mechanism. I was no longer just a heater; I was an automatic machine. You could set the timer for how dark you wanted your toast, and when the time was up, the heating elements would shut off, and a spring would launch the finished slice into the air with a satisfying 'pop!'. This was revolutionary. No more watching, no more flipping, no more burnt bread. I had become the automatic pop-up toaster. I felt like a superstar. That simple, delightful 'pop' was the sound of convenience, the sound of a problem solved through cleverness and perseverance. It echoed in kitchens everywhere, changing breakfast forever.

A lot has changed since Charles Strite gave me my pop. From that initial spring-loaded marvel, I have continued to evolve. My journey took me from a simple wire cage to a sleek, essential appliance in nearly every home. I learned new tricks along the way. Designers gave me wider slots, perfect for toasting thick slices of bread or a chewy bagel. Engineers gave me special settings, like a defrost function to gently thaw a frozen waffle or a reheat button to warm up a forgotten slice without burning it. I come in countless shapes, sizes, and colors now, from shiny chrome that reflects the whole kitchen to bright reds and blues that add a splash of personality. But through all these changes, my core purpose has remained the same. I am here to bring a little bit of simple, reliable warmth to the start of your day. My story is a reminder that even a small invention, born from a simple frustration like burnt toast, can grow and change the world in its own small way, one perfectly golden-brown slice at a time.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.