The Emperor's New Clothes

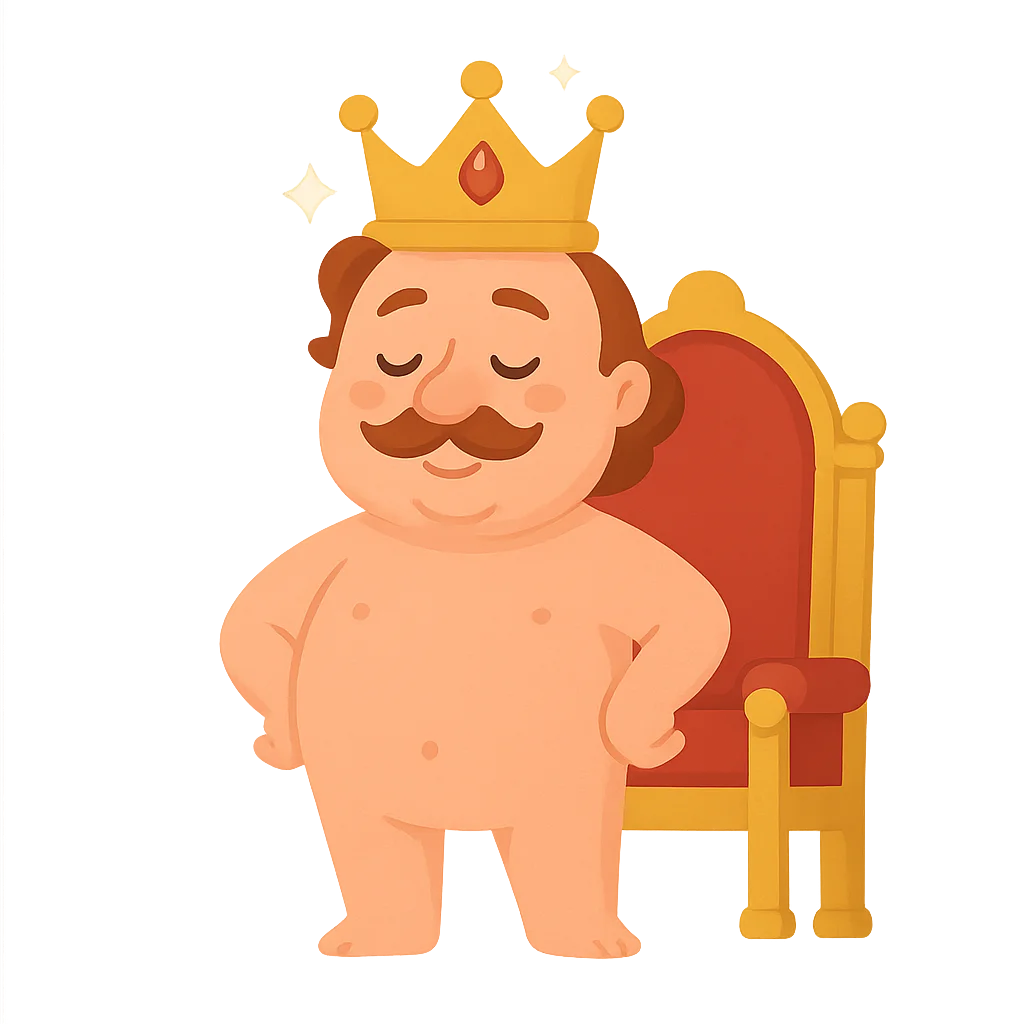

My name isn't important, not really. I was just one of the many children who played in the cobblestone streets of our grand capital, a city that gleamed with polished brass and whispered with the rustle of expensive silks. Our Emperor was a man who loved clothes more than anything—more than parades, more than wise counsel, and certainly more than his people. This is the story of how that love for finery led to the most embarrassing day of his life, a tale you might know as The Emperor's New Clothes. The air in our city always hummed with a strange kind of pressure, the need to look perfect and say the right thing. The Emperor spent all his money on new outfits, one for every hour of the day, and his councilors spent all their time admiring them. It felt as if the entire city was a stage, and everyone was performing, afraid to be the one who didn't fit in. I used to watch the royal processions from my window, seeing the endless parade of velvet, gold thread, and jewels, and wonder if anyone was ever truly honest about what they thought. His obsession was so profound that matters of state were often discussed in his wardrobe, between fittings for a new pair of trousers or the selection of a new jeweled collar. The city's economy didn't thrive on trade or agriculture, but on tailoring, weaving, and jewel-setting. To be a successful citizen was to be a fashionable one. This collective delusion meant that honesty was a rare and dangerous commodity. We were all so busy pretending, so caught up in the performance of admiration, that we forgot how to see things as they really were. Our world was built on a fragile foundation of silk and compliments, and I always had a feeling that one day, it would all unravel.

One day, two strangers arrived in the city. They weren't dressed in finery but carried themselves with an air of immense confidence that made even the royal guards take notice. They called themselves master weavers, claiming they could create the most magnificent cloth imaginable, a fabric so light it felt like wearing air and so colorful it captured the essence of a rainbow. But their sales pitch had a clever, wicked twist. This cloth, they announced in the public square, was not only beautiful but also magical: it was completely invisible to anyone who was unfit for their office or unforgivably foolish. The Emperor, whose greatest fear was being perceived as anything less than perfect, was immediately captivated. He imagined himself in a suit that could instantly reveal which of his officials were incompetent. He hired them on the spot, giving them a grand room in the palace, chests full of gold thread, and the finest silk money could buy. Days turned into weeks. The swindlers made a great show of working, their empty looms clacking away day and night. They would describe the stunning patterns and vibrant colors to anyone who visited, speaking of 'celestial blues' and 'fiery scarlets'. The Emperor, growing impatient, sent his most trusted old minister to check on their progress. The poor man entered the room and stared at the empty looms, his heart pounding in his chest. He couldn't see a single thread. Panic seized him. 'If I admit I see nothing,' he thought, 'the Emperor will think I am unfit for my position. I will lose everything.' So, with a trembling voice, he praised the non-existent fabric lavishly. “Oh, it is exquisite. The patterns are simply divine.” A second official was sent, and he, too, faced the same dilemma and told the same lie. Soon, the whole city was buzzing with talk of the wondrous, invisible clothes, and everyone pretended they could see them, each person terrified of being thought a fool by their neighbors. I heard the whispers in the market, the grand descriptions of colors like sunset and patterns like starlight, and I felt a knot of confusion in my stomach. How could everyone see something I couldn't even imagine?

Finally, the day of the grand procession arrived, a day meant to show off the Emperor's spectacular new suit. The two swindlers, with great ceremony, mimed dressing the Emperor. 'Here are the trousers,' they'd say, pretending to hold up shimmering fabric. 'And here is the royal robe.' The Emperor, stripped to his undergarments, felt a dreadful chill, both from the air and from the dawning suspicion in his heart. But he couldn't back down now. His chamberlains pretended to lift the long, invisible train as he stepped out into the streets. A hush fell over the crowd, a collective breath held in terrified pretense, followed by a wave of forced applause. 'Magnificent.' 'Exquisite.' 'What a fit.' everyone cried, their voices strained. Everyone but me. I stood with my parents, squeezed into the front row, and all I saw was the Emperor walking around in his underwear. It wasn't magnificent; it was just silly. Before I could stop myself, the words tumbled out of my mouth, clear and loud: 'But he hasn't got anything on.' A ripple of silence, then a titter, then a wave of laughter swept through the crowd as my words were repeated from person to person. 'The child is right. He has nothing on.' The Emperor shivered, realizing the awful, naked truth, but he held his head high and continued the procession to the very end. The two swindlers were long gone, their pockets full of gold. The story, first written down by the great Danish author Hans Christian Andersen on April 7th, 1837, became more than just a funny tale about a vain ruler. It became a reminder that sometimes the truth is simple, and it takes the honesty of a child to say what everyone else is too afraid to admit. This story doesn't just live in old books; it lives in cartoons, in sayings we use today like 'the emperor has no clothes,' and in the courage it takes to speak up for what you know is right, even when you're standing all alone.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.