The Great Connection

Have you ever paused to wonder where the boundless energy for a lion’s thunderous roar or a rabbit’s lightning-fast hop truly comes from? It all begins with a star, our sun, bathing the world in light and warmth. I am the process that allows a tiny seed to catch that sunlight and weave it into sugary fuel, an amazing trick called photosynthesis. When a rabbit nibbles on a clover leaf, that captured sun-energy moves into its body. And if a cunning fox catches that rabbit for its dinner, the energy moves once more. I am this invisible river of energy, flowing from one living thing to the next, connecting the smallest microbe in the soil to the mightiest eagle soaring high above. Before you knew my name, you simply knew my rules: to live is to eat. I am the secret that organizes the entire planet into a cosmic lunch line, ensuring that energy flows from the bottom all the way to the top.

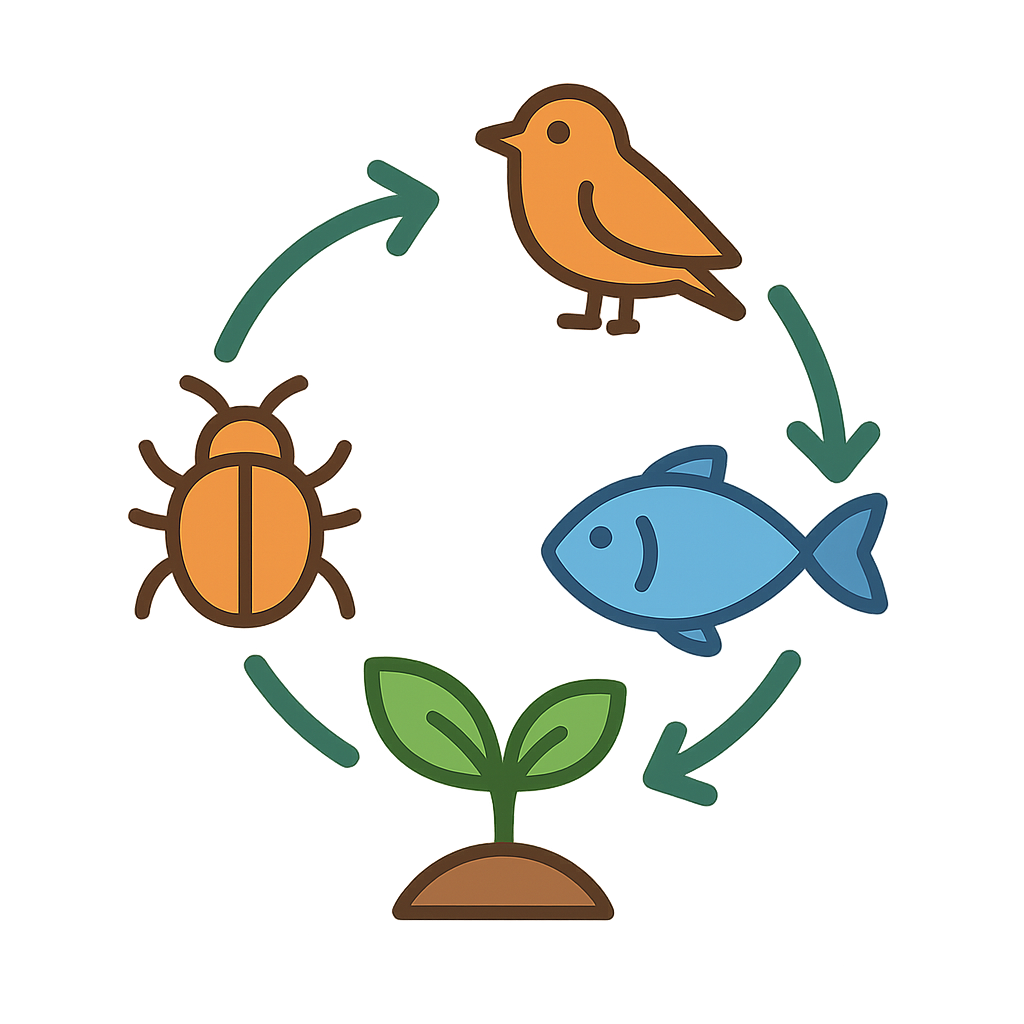

For millennia, people observed my patterns without knowing what to call me. They saw hawks hunting field mice and bears scooping fish from rivers; it was simply the way of the world. But deep thinkers began to write my story down. Around the 9th century, a brilliant scholar in Baghdad named Al-Jahiz meticulously documented the lives of animals. He wrote about how mosquitoes are food for flies, and how flies, in turn, become food for lizards and birds. He was one of the very first to describe my links in writing. It took many more centuries, however, until an English ecologist named Charles Elton gave me my official name in 1927: the Food Chain. He drew simple, clear diagrams showing who eats whom, making my complex rules understandable for everyone. He explained that every living thing has a job. There are the “producers,” like plants, who make their own food. Then come the “consumers,” the animals who must eat to live. Herbivores eat plants, carnivores eat other animals, and omnivores, like you humans, eat both. And when everything dies, the “decomposers”—tiny bacteria and elegant fungi—break it all down, returning precious nutrients to the soil. It is nature’s perfect recycling program.

My connections are powerful, but they are also incredibly delicate, like the threads of a spider’s web. If you remove a single link, the entire structure can wobble and collapse. Consider the story of the Pacific Ocean’s kelp forests. In that world, sea otters adore eating sea urchins. Sea urchins, in turn, devour the giant kelp that creates breathtaking underwater forests, home to thousands of species of fish and invertebrates. For a time, humans hunted sea otters for their luxurious fur until they nearly vanished. Without the otters to keep them in check, the sea urchin population exploded. They munched and crunched their way across the ocean floor, transforming lush kelp forests into desolate, rocky landscapes called “urchin barrens.” All the creatures who depended on the kelp for food and shelter disappeared. When scientists discovered this connection, people began to protect the sea otters. As the otters returned, they started eating the urchins, and the beautiful kelp forests slowly began to grow back. The sea otter is what scientists now call a “keystone species”—a single, crucial link that holds the entire chain together.

While “food chain” is a simple and useful name, it doesn’t quite capture my full complexity. In reality, I am much more like a giant, tangled, and beautiful Food Web. A red fox, for example, doesn’t only eat rabbits. It might also feast on summer berries, hunt for mice, or snack on insects. A great horned owl living in the same forest might compete for those very same mice. A black bear might eat the same berries as the fox but will also catch fish from a stream. You see, almost every animal is a part of several different chains, and all of these chains cross and interlace, weaving an intricate web of life. This complexity is my superpower. It makes ecosystems resilient. If the rabbit population declines one year due to a harsh winter, the fox has other food sources to rely on. This intricate design helps life adapt and thrive even when faced with challenges and change.

So, where do you fit into this great, interconnected story? You are a vital part of my global food web. Every time you enjoy a crisp apple, a fresh salad, or a chicken sandwich, you are taking in energy that began its journey 93 million miles away in the heart of the sun. The choices you and all other humans make have a profound impact on every one of my links, from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains. By understanding how I work, you can help protect me. You can support efforts to keep oceans clean for the fish, forests healthy for the bears, and the air pure for the plants that form my foundation. I am the story of connection, the endless cycle of life, death, and rebirth. By learning my story, you become one of my most important guardians, helping to ensure that the beautiful, complicated dance of life continues for all the generations to come.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer