I Am the Drone: An Eye in the Sky

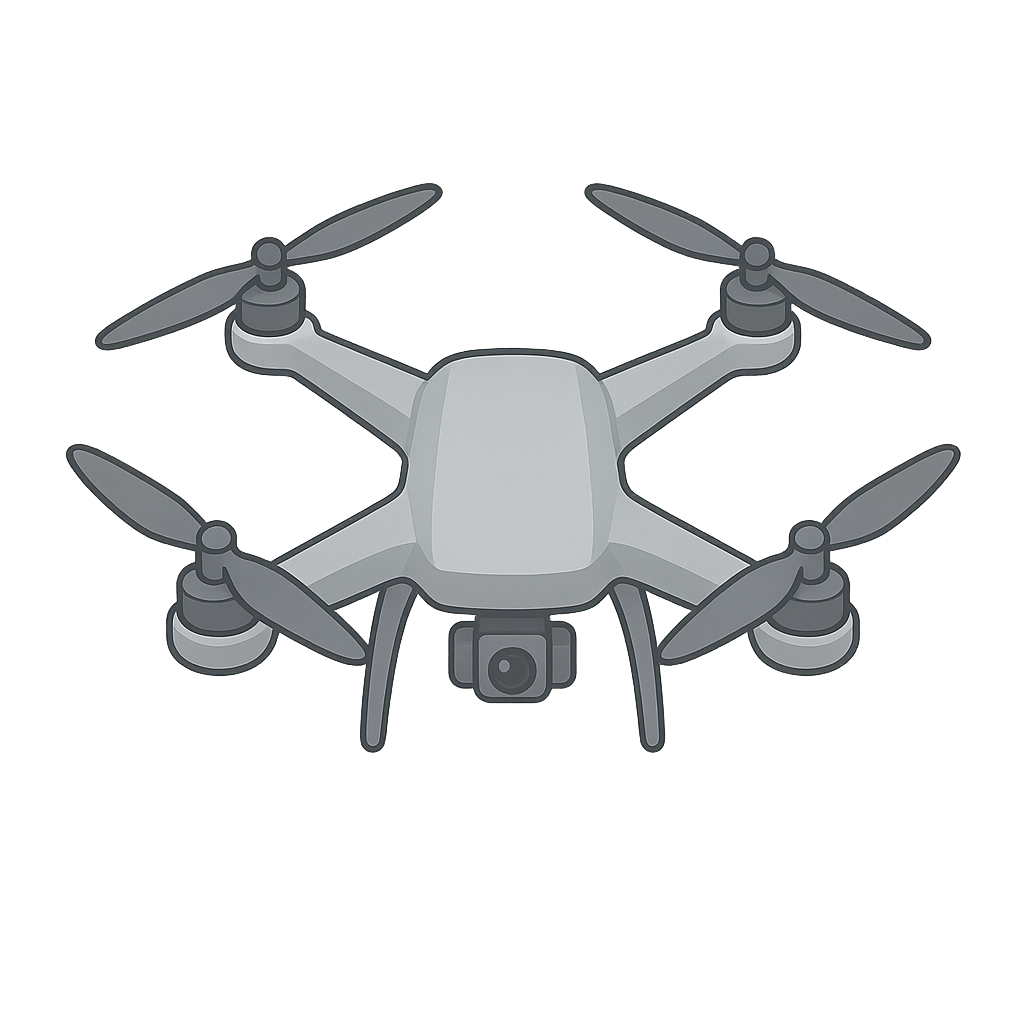

Hello from up high. The world looks so different from here. I can race the wind, dance with the clouds, and see everything like a giant, living map spread out below. You probably call me a drone, but my official name is an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, or UAV for short. It's a fancy way of saying I can fly all by myself, without a pilot sitting inside me. I zip through the air, my propellers humming a steady tune, capturing breathtaking views with my camera-eyes. People use me to see places they can’t reach, to create amazing videos, or even to deliver packages right to their doorstep. It might seem like I just appeared in your world recently, a product of sleek smartphones and powerful computers. But my story, my family's story, started long before any of that. My roots stretch back over a century, to a time of steam engines and flickering gas lamps, when the very idea of a machine flying on its own was the stuff of science fiction. My journey from a simple idea to the high-tech friend you see today is one of patience, cleverness, and a whole lot of trial and error. Before I could become a filmmaker or a delivery service, my ancestors had to learn how to fly, and that story begins a long, long time ago.

My earliest whispers began in the mid-19th century. Imagine, all the way back in 1849, the Austrian Empire tried to send unmanned balloons carrying bombs over the city of Venice. They were simple, carried by the wind, and not very accurate, but the idea was there: a flying machine with a mission, but no pilot. However, my true family tree began to sprout during World War I. A brilliant British inventor named Archibald Low was working on a secret project. In 1916, he created one of my first direct ancestors, the 'Aerial Target.' It was a small, radio-controlled plane designed to be a practice target for anti-aircraft gunners. It was tricky work. Radio signals weren't very reliable back then, and many of my early relatives crashed. But Professor Low proved that it was possible to guide a machine through the air from the ground. He planted the seed of an idea that would grow for decades. Then came the moment I got my name. In 1935, the British Royal Navy needed a better target plane. They took a popular pilot-training biplane, the De Havilland Tiger Moth, and modified it to be radio-controlled. They called this new version the DH.82B 'Queen Bee.' The pilots and sailors training with it needed a simple name for these pilotless targets that buzzed through the sky. Thinking of the male bee that follows the queen, they started calling the successors to the Queen Bee 'drones.' The name stuck. For many years, that was the main job for my family: to be drones, buzzing targets for military training. It wasn't a glamorous job, but it was important. We were helping people learn and prepare, and with every flight, my creators learned more about how to make us fly better, respond faster, and stay in the air longer. We were the humble, buzzing pioneers of the sky.

My 'teenage' years, through the middle and late 20th century, were spent almost entirely in military service. I grew bigger, flew higher, and went on missions that were too dangerous for human pilots. My main job was reconnaissance—flying secretly over areas to gather information with my cameras. I was a silent eye in the sky. But I was still just a remote-controlled plane, always needing a human on the ground telling me exactly where to go. I didn't have a mind of my own. That all started to change because of a man named Abraham Karem. In the late 1970s, working in his garage in California, he dreamed of creating a drone that could stay in the air not just for hours, but for days. He was called the 'Drone-father' for a reason. His creations, like the Albatross and later the Amber, were revolutionary. They were lightweight and incredibly efficient, and his work directly led to the famous Predator drone that could fly for over 40 hours. But the biggest change for me, the moment I truly started to get smart, happened in the 1990s. This was when the Global Positioning System, or GPS, became fully operational and available. Suddenly, I had a brain. GPS was like an invisible map of the entire world and a compass that always knew where I was. For the first time, I could be given a flight path—a series of coordinates—and I could fly it all by myself, without a human constantly steering me. I could navigate, hold my position against the wind, and even return home on my own if I lost contact. This was true autonomy. At the same time, all the things that make me work were getting smaller, lighter, and more powerful. Computers that once filled a room could now fit on a tiny circuit board. Cameras became sharper yet smaller. Sensors that could detect heat or measure distance became light as a feather. This combination of a GPS 'brain' and tiny, powerful parts was the magic recipe that would allow me to leave my military past behind and fly into the public world.

The beginning of the 21st century was when my world truly opened up. The technologies that made me smart—GPS, tiny computers, and lightweight sensors—became so inexpensive and common that inventors and hobbyists could finally get their hands on them. I was no longer a million-dollar military secret. I was ready to find new jobs and help people in their everyday lives. My transformation was incredible. I went from being a spy in the sky to a helper on the ground. Today, you can see my cousins everywhere. Some of us are zipping through cities, testing ways to deliver packages and medicine right to your door. Others are flying over vast farmlands, using special cameras to help farmers see which crops need more water or fertilizer, helping them grow more food with less waste. When disaster strikes, my bravest relatives fly into dangerous situations. They help firefighters find hot spots in a raging wildfire or assist search-and-rescue teams in finding lost hikers in the mountains, going where it’s too risky for people. And, of course, you’ve seen my work in movies. I am the artist of the sky, capturing those stunning, sweeping shots that used to require a helicopter and a massive budget. My story is no longer just about military targets or secret missions. It's a story of human imagination. I am a tool, and what I can do is limited only by the creativity of the people who use me. From a simple buzzing target to a filmmaker, a farmer’s assistant, and a lifesaver, my journey has been amazing. And the best part is, my story is still being written, every day, by people like you who look to the sky and imagine what’s next.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.