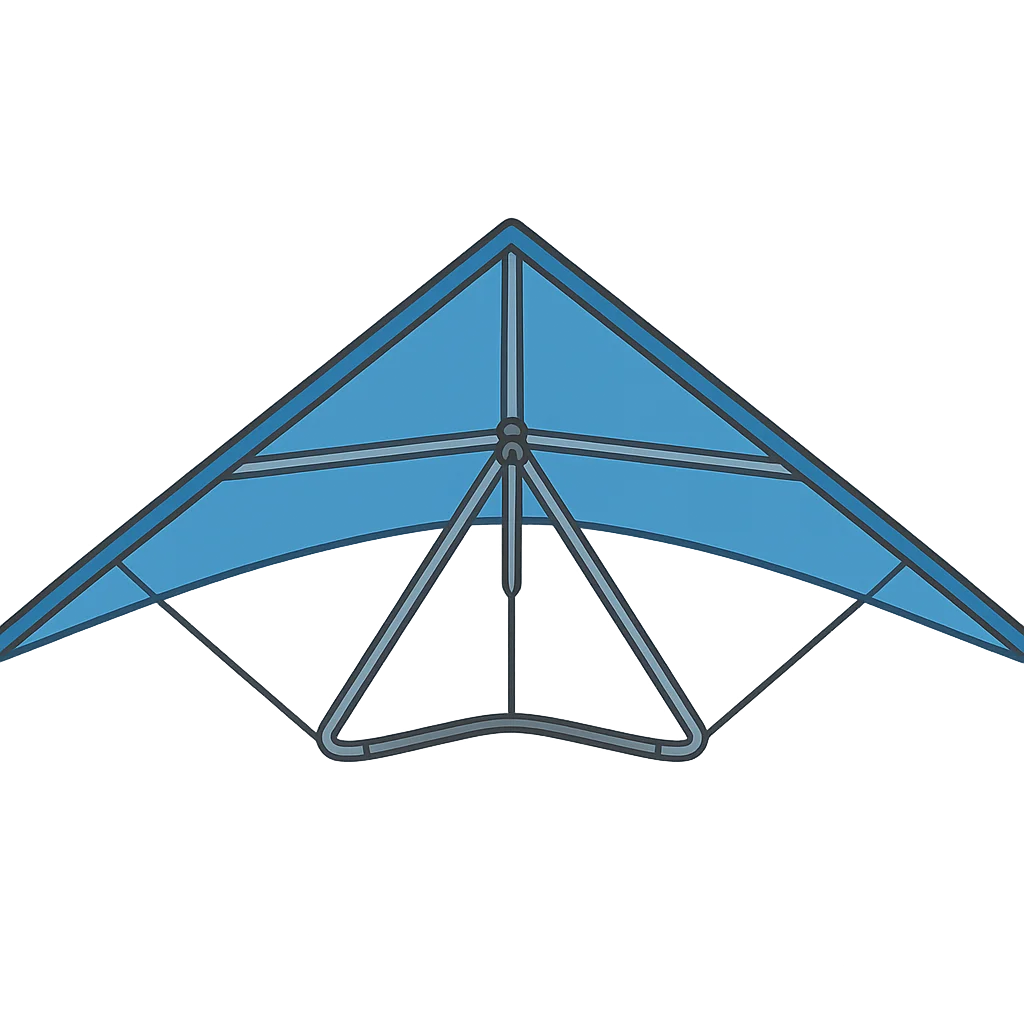

I am the Glider

Before the roar of engines filled the sky, there was only a whisper. I am that whisper. I am the Glider, the physical shape of a dream as old as humanity itself—the dream of soaring with the birds, of touching the clouds with nothing but wit and courage. For centuries, people looked to the sky and wished, but they didn't understand the invisible forces that held an eagle aloft. That began to change with a brilliant man named Sir George Cayley. He saw what others missed. He realized that flight wasn't magic; it was science. He understood the delicate balance of lift, drag, and thrust. In 1853, after years of sketching and studying, he brought me to life. I was a simple thing of wood and canvas, but I held a universe of possibility. My moment came on a grassy hill in Yorkshire, England. Sir Cayley's coachman, a man more comfortable with horses than with heights, was my first pilot. With a push, I surged forward, caught the wind, and for a few breathtaking moments, we flew. We soared across a small valley, suspended between earth and sky. It was a short journey, but it was monumental. For the first time, a person had flown in a machine that was heavier than air. I had proven that the whisper on the wind could become a reality. The dream was no longer just a dream; it had taken flight.

Decades later, my journey took me to Germany, into the hands of a man who would become known as the 'Glider King,' Otto Lilienthal. In the 1890s, he didn't just want to build one of me; he wanted to perfect me, to truly understand how to dance with the air. I became many things for him—a series of over a dozen designs, each one inspired by the elegant curve of a stork's wing. He would carry me to the top of a hill he built just for our flights, and together, we would run into the wind and leap into the sky. Flying with Otto was an intimate partnership. He had no complex controls, no rudder or stick. He controlled my path by shifting his body, dangling his legs to steer me left or right, leaning forward to gain speed. It was pure instinct, a connection between man, machine, and nature. We must have been a sight, a man with magnificent wings soaring over the German countryside. We flew over 2,000 times together, each flight a lesson. Otto was a meticulous scientist. He documented everything, taking photographs and writing detailed notes about our flights. He wasn't just flying for himself; he was creating an instruction manual for all who would follow, proving that practice and observation were the keys to unlocking the sky. He showed the world that gliding wasn't a fluke but a skill that could be learned and mastered.

My most famous chapter began at the turn of the century, on the windy shores of North Carolina. Two brothers from Ohio, Wilbur and Orville Wright, had read about Otto Lilienthal's work and were determined to solve the final puzzles of flight. They brought me to a place called Kitty Hawk, where the steady winds were perfect for testing. From 1900 to 1902, I became their tireless teacher. The Wrights were different from my previous companions. They were methodical, leaving nothing to chance. When they realized the existing data on wing shapes was unreliable, they built a small wind tunnel in their bicycle shop to test hundreds of my potential wing designs themselves. Their greatest breakthrough came from watching buzzards circle in the sky. They noticed the birds twisted the tips of their wings to stay balanced. This observation led them to invent 'wing-warping,' a brilliant system of cables that allowed the pilot to twist my wings, just like a bird. This was the key to true control in the air. For three years, they flew me again and again, first as an unpiloted kite and then with one of them aboard, lying flat on my lower wing. I was their laboratory. I crashed, I was repaired, and I flew again. Each flight, each bumpy landing, taught them something new about balance, steering, and control. I was the final, critical step before they dared to add an engine. I was the silent school where humanity learned to fly.

My purpose was not to remain silent forever. My quiet flights were the necessary prelude to something much louder. The lessons the Wright brothers learned from me at Kitty Hawk gave them the confidence and the knowledge they needed to take the next step. On December 17th, 1903, my direct descendant, the Wright Flyer, fitted with a small, sputtering engine and propellers, lifted off the sand. The whisper had become a roar. That first powered flight lasted only twelve seconds, but it changed the world forever, and it was born from the knowledge I had provided. My story did not end there, however. I am the ancestor of every airplane, from the smallest prop plane to the largest jet. But I also live on in my original form. Today, people still fly gliders, not to get somewhere fast, but for the pure, silent joy of soaring. They ride the thermal updrafts, climbing high into the sky to experience the same magic my first pilots felt. I am the beautiful, foundational idea of flight—a reminder that sometimes the grandest journeys begin not with a roar, but with a quiet and determined whisper on the wind.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.