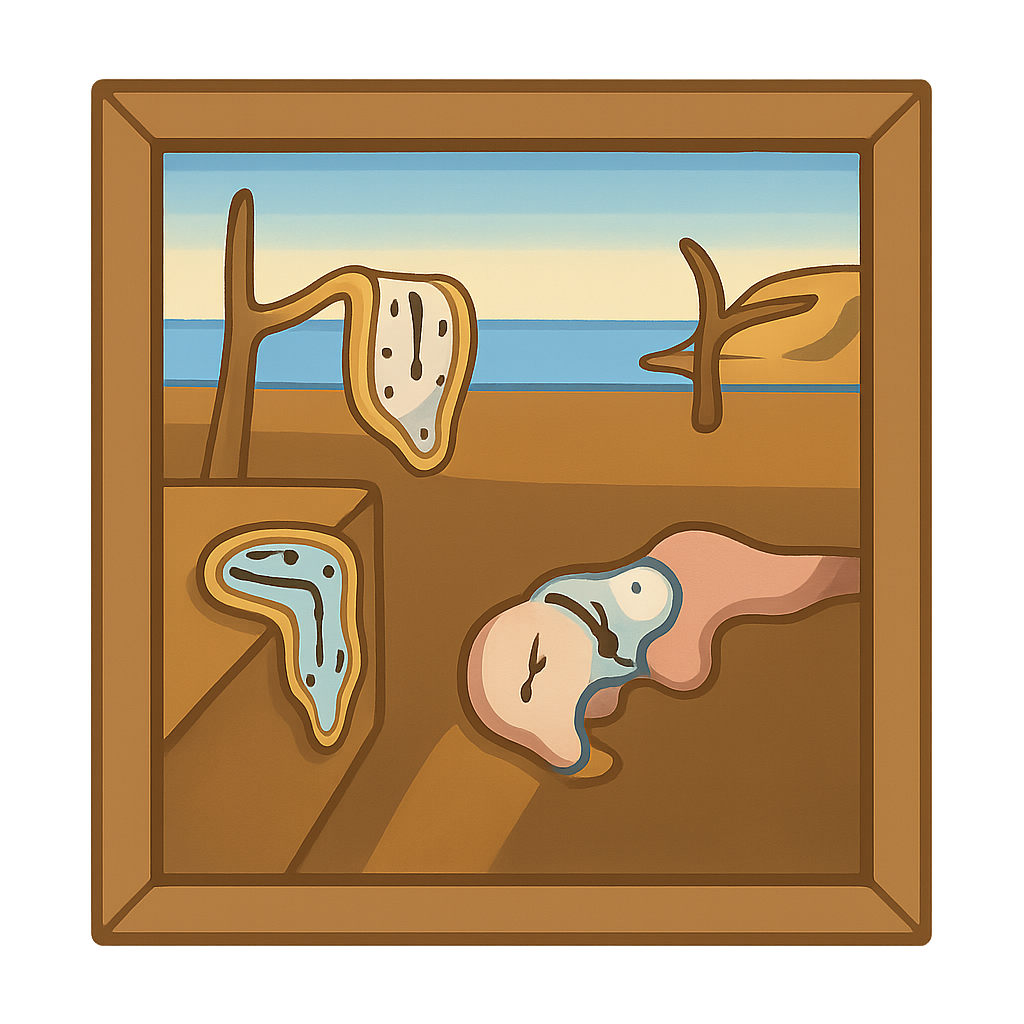

The Persistence of Memory

Imagine a world where time itself melts like ice cream on a hot day. That is where I was born. It is a place bathed in a strange, golden light, the kind you see just before the sun vanishes or right as it peeks over the horizon. The air is perfectly still, and the only sound is a profound, echoing silence. It feels like a dream you are trying desperately to hold onto after waking up. In this quiet landscape, beside a sea as calm and flat as glass, you will find me. I show you clocks, but they are not like any you have ever seen. They are soft, gooey, and limp, draped over the branch of a dead olive tree as if they were laundry left out to dry. Another one slides off the edge of a blocky platform, and a third rests upon a bizarre, sleeping creature that looks like it washed ashore from the depths of a strange ocean. Not all time is soft here. A single, hard pocket watch sits face down, its shiny orange surface swarming with black ants, a tiny, unsettling island of decay in this timeless world. Have you ever had a moment in your life that felt like it lasted forever, or a whole year that seemed to pass in the blink of an eye. That is the feeling I capture. I am not a real place, but a feeling made visible. I am a painted dream. My name is The Persistence of Memory.

My creator was a man whose imagination was as famous and as wonderfully peculiar as his magnificent, upturned mustache. His name was Salvador Dalí, and he was a master of making dreams real. He painted me in the summer of 1931, in his small fisherman's cottage in Port Lligat, a coastal village in Catalonia, Spain. The stark cliffs and endless sea you see in my background were the views from his own window, but he transformed them into a stage for the subconscious. The story of my creation is almost as strange as I am. One evening, Dalí was feeling unwell with a headache while his wife, Gala, went out to the cinema. For dinner, they had eaten a very soft, very runny Camembert cheese. As he sat at his table, staring at the leftover cheese melting under the warm lights, a vision struck him. He saw clocks, not made of metal and glass, but of the same soft, drooping substance as the cheese. He knew immediately what he had to paint. Dalí was a leader of an art movement called Surrealism, which explored the irrational and illogical world of dreams. Surrealists believed that the subconscious mind held a deeper truth than our waking reality. Dalí developed a technique he called the 'paranoiac-critical method,' where he would put himself into a dream-like state to access visions from his mind, which he would then paint with incredible precision. He called his paintings 'hand-painted dream photographs,' and that is exactly what I am: a snapshot of a thought, an image pulled directly from the deepest, most mysterious corner of his mind.

People have spent decades looking at me, trying to solve my puzzle. What do I mean. Dalí himself was famously mysterious about my purpose, preferring that each person find their own meaning in my strange world. But I can share some of the secrets he painted into me. My famous melting clocks are a challenge to the rigid, unbending idea of time we live by every day. In our memories, in our dreams, time is not a straight line. It is fluid, subjective, and elastic. A happy memory can feel like a fleeting moment, while a moment of fear can stretch into an eternity. My soft clocks represent this psychological time, which Dalí found far more interesting than the ticking of a mechanical clock. The hard clock, covered in ants, represents the opposite. The ants were a symbol Dalí often used to signify decay, death, and the unstoppable march of physical reality. It is a reminder that while time may feel flexible in our minds, in the real world, it leads to an inevitable end. And what of the strange, fleshy creature asleep on the sand. Many believe it is a self-portrait of the dreamer himself, Salvador Dalí, his form distorted and vulnerable as he lies lost in his own subconscious creation. I invite you to look at my silent shores, my still sea, and my strange objects, and ask yourself: what does time feel like to you.

My journey did not end in that small Spanish cottage in 1931. A year later, in 1932, I was shown at a gallery in Paris and soon after made the long voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1934, I found my permanent home in a very important place: the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Here, millions of people from every corner of the globe have stood before me, their faces reflecting in my varnish. They get lost in my quiet, bizarre landscape, and for a moment, they leave the busy city behind and enter a world governed by dreams. My image has traveled far beyond the museum walls. You may have seen my melting clocks in cartoons, on posters, or in movies. I have become a universal symbol for anything strange, surreal, or wonderfully weird. But I am more than just paint on a small canvas. I am a reminder that the human mind is the most incredible landscape of all. I teach everyone who looks at me that it is good to question reality, to explore our dreams, and to embrace the power of our imagination. I am proof that we can see the world not just as it is, but as it could be in our wildest, most persistent memories.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer