The Story of the Wrench

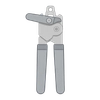

You’ve probably seen me hanging on a pegboard in a garage, nestled in a toolbox, or clutched in the hand of someone determined to fix something. I am the Wrench. My body is forged from hard, cool steel, designed for strength and leverage. But my real secret, the thing that makes me special, is my jaw. Unlike my cousins, the spanners, who only fit one specific size, my jaw can open wide or close tight with a simple turn of a screw. I was born from a common frustration. Imagine a world filled with countless nuts and bolts, each a slightly different size. Before I came along, you needed an entire collection of tools, a heavy bag of fixed-size spanners, just to do a simple job. It was inefficient and cumbersome. People needed a single, adaptable tool that could handle many jobs. They needed a hero for their toolbox, one that could change its shape to fit the problem at hand. I became that hero, the one-size-fits-most solution that made building, repairing, and inventing so much easier for everyone.

My story, however, began long before I had my familiar shape. My ancestors were simple, solid pieces of metal, each crafted for a single purpose. They did their jobs well, but the world was changing rapidly in the early 19th century. The air buzzed with the sound of new machines, steam engines chugged along newly laid tracks, and factories were rising toward the sky. In this age of mechanical wonder, a man named Solymon Merrick saw the problem of the cluttered toolbox and imagined a better way. He lived in Springfield, Massachusetts, and was a clever inventor who thought deeply about how to improve everyday tools. He dreamed of a single spanner that could adjust to grip different sizes. It was a revolutionary idea. After much thought and tinkering, he designed a tool with a movable jaw that slid along a rack. On August 17th, 1835, his hard work was officially recognized when he was granted a patent for his invention. A patent is a special document from the government that protects an inventor’s idea, ensuring no one else can copy it for a certain period. For a world just entering the Industrial Revolution, my creation was a groundbreaking concept. I represented efficiency and ingenuity, a single tool that could help build and maintain the complex machinery that was changing the world.

While Solymon Merrick gave me life, my journey of improvement was far from over. Decades passed, and I served faithfully, but I knew I could be even better. My next great leap forward came in the early 20th century, thanks to a Swedish immigrant named Karl Peterson. He was a brilliant blacksmith working for the Crescent Tool Company in Jamestown, New York. Peterson looked at the existing designs and saw room for perfection. He refined my adjustment mechanism, introducing a diagonal-toothed worm screw that made my jaw stronger, more stable, and incredibly easy to adjust with just the flick of a thumb. This new design, which was first produced in 1907, was sleeker and more reliable than anything that had come before. This perfected version of me arrived at the perfect time. The automobile industry was booming, and Henry Ford’s assembly lines were churning out cars at an astonishing rate. My ability to quickly adjust to fit various nuts and bolts made me an indispensable tool for the workers building those cars. I was no longer just a clever gadget; I was an essential part of the engine of progress, helping to build the machines that would connect the country and define a new era of manufacturing.

Looking back, my journey has been incredible. I am more than just a piece of steel; I am a symbol of human ingenuity and the relentless drive to find better solutions. My metallic hands have helped assemble the first automobiles that roamed the highways, tightened the bolts on towering skyscrapers that scraped the clouds, and even secured components on rockets that ventured into the vastness of space. Today, I am as relevant as ever. You’ll find me under kitchen sinks fixing leaky pipes, in workshops helping to build furniture, and in the hands of cyclists tuning their bikes for a ride. I empower people every day, giving them the ability to build, create, and repair their own world. My story is a reminder that sometimes the most powerful changes come from the simplest ideas. It’s a lesson in adaptability—the importance of being able to adjust to new challenges. From a simple concept to a tool that helped build the future, I stand as proof that with a little creativity and perseverance, one good idea can truly change everything.

Activities

Take a Quiz

Test what you learned with a fun quiz!

Get creative with colors!

Print a coloring book page of this topic.